Four of ten American seniors live alone

Living alone predicts poorer health outcomes for younger seniors

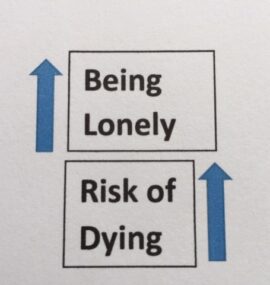

Living alone might be a suitable proxy for loneliness or inadequate social support, both of which diminish health and well-being. Would living alone predict increased risk of dying or developing cardiovascular disease? A large, international team of researchers used data from 44,573 participants with a median age of 71 years in the global REACH study to find out.

Over follow-up of up to four years and after accounting for confounding factors, participants between the ages of 45-65 and 66-80 who lived alone had significant 24 and 12 percent higher risks of dying, respectively, compared to participants who did not live alone. Living alone did not predict higher risk of dying for participants older than 80 years. Except for the oldest seniors, living alone predicted higher risk of dying, even over a follow-up of just four years.

Were the results of the REACH study a fluke? Researchers in San Francisco found similar results using data for 1,604 participants with an average age of 60 in the Health and Retirement Study. Participants were asked if they felt left out, or lacked companionship, or felt isolated on a three-point scale. Loneliness was defined as reporting “some of the time” or “often” for any of the three questions.

After four years of follow-up and after accounting for sociodemographic and health confounding factors, lonely participants had a significant 44 percent higher risk of dying compared to not lonely participants. In addition, lonely participants reported a significant 59 percent higher risk of impaired activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, and toileting. Similarly, compared to not lonely participants, lonely participants had 28 percent higher risk of having greater difficulty lifting or carrying items weighing more than 10 pounds and 31 percent higher risk of having difficulty climbing one flight of stairs. Loneliness is a subjective feeling of isolation and may be a more accurate measure psychosocial distress than the number of social connections or simply living alone.

Previous research studying the links between loneliness and mortality did not control for self-reported physical and mental health. Researchers in Australia used data from 3,486 participants age 49 or older in the Blue Mountain Eye Study and for whom self-reported health data were available. Compared to participants who did not live along, participants younger than age 75 who lived alone had a significant 36 percent higher risk of dying during 10 years of follow-up, independent of health status. Living alone predicted greater risk of dying for younger seniors.

Elderly people who live alone may disproportionately experience loneliness and social isolation compared to elders who live with others. In Sweden, half of the women and a quarter of the men over age 65 live alone. European researchers used data from 2,404 participants with an average of 78 years in the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Kungsholmen to see if living alone predicted increased risk of dying or being institutionalized in a nursing home.

Compared to men participants who lived with someone, men who lived alone had a significant 44 percent higher risk of dying over six years of follow-up. Women who lived alone did not have a higher risk of dying. In addition, participants (men and women) who lived alone had a significant 63 percent higher risk of ending up in a nursing home at the end of follow-up. The relatively high rate of nursing home care might reflect, in part, the fact that the Swedish social welfare system helps defray the cost of nursing homes.

Older adults who live alone can increase their risks of adverse health outcomes. The presence of social support predicts greater likelihood of positive health outcomes. Under what circumstances does social support improve health for seniors living alone? Scientists in California used data from 4,772 older adults with an average age of 73 years in the Health and Retirement study to find out. The presence of social support was determined from the answer to a single question that asked if the participant had relatives or friends, aside from a spouse or partner, who could help out with basic care activities over a long period of time (yes or no). Outcomes of interest included activities of daily living dependency, nursing home stay of 30 days or more, and death.

During 5 years of follow-up, 3,013 participants experienced a health shock (hospitalization, new diagnosis of cancer, stroke, heart attack). The absence of social support predicted significantly increased risk of a 30 day or more nursing home stay (14.2 versus 10.9 percent) but only in the setting of a health shock. Social support was not linked to risk of death or becoming dependent on others for activities of daily living Antidotes to loneliness include greater social engagement and satisfying social relationships. If you live alone it behooves you to Cultivate Social Connections.